- Home ›

- Irish prison records ›

- History of Irish prisons

A brief history of prisons in Ireland

The notion of prisons as places to hold or punish criminals after they've been tried and convicted is relatively modern. At the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, prisons were set up to hold people before and until their trial.

There wasn't a need for a cell after a guilty verdict because the sentence was usually corporal – whipping, execution – or involved transportation. There simply weren't any alternatives. Only debtors were held in prison for any length of time, until their families or friends rounded up the money to repay the debt.

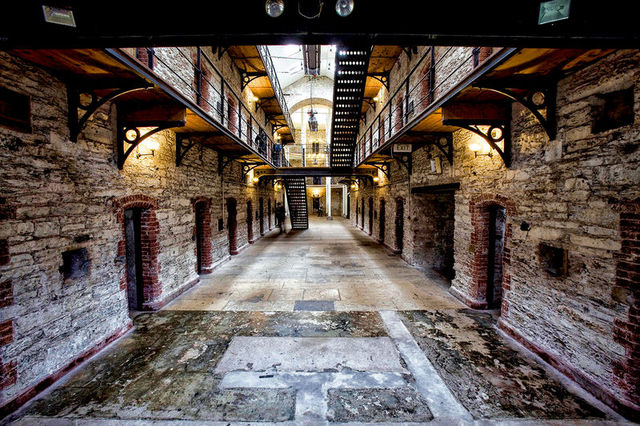

Cork City Gaol

Cork City GaolAs a place of pre-trial detention, early prisons in Ireland ranged from the local bridewell, a small building made up of cells typically attached to a local police station or courthouse, to full blown gaols in large towns and cities. They had one thing in common: they were ghastly, usually little more than a rat-infested black hole.

Over time, the idea of reform started to enter the debate. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham (a pretty cool guy for his time... he believed in gender equality, animal rights, the separation of church and state, the abolition of slavery and corporal punishment, and the decriminalisation of homosexuality) was one of the most important figures in this radical shift. He believed that if criminals were given hard work and education in prison they would become productive members of society, and he designed prisons to accommodate his methods.

The first of the new progressive prisons opened as Richmond General Penitentiary in 1820 in Grangegorman, Dublin. It was intended as an alternative to transportation and to specialise in reform rather than punishment.

Kilmainham Gaol Dublin - entrance

Kilmainham Gaol Dublin - entrance Kilmainham Gaol Dublin - entrance

Kilmainham Gaol Dublin - entranceAlthough it had its problems and was fairly quickly closed as a prison and turned into an asylum, the movement against unproductive punishment had taken hold.

Standards of bedding, clothing and food were improved, but would hardly be considered humane nowardays.

Despite these improvements in conditions, transportation continued to be widely used as a sentence. More than 27,258 people were transported to Western Australia between 1837 and 1846, and just shy of 12,000 between 1847 and 1856.

it would be nice to think that the decline in numbers was due to greater acceptance of the reformist approach; in fact, it had more to do with the number of complaints from the colony about the calibre of prisoners sent to it.

In 1853, the sentence of transportation was replaced with penal servitude and, for the first time, criminals started to serve long sentences in Irish prisons. Problem was, the capacity of Irish prisons at this time was about 2,900 while the immediate number of offenders incarcerated totalled more than 3,500.

A year later, the Convict Prisons Board was set up and introduced a completely new system which saw a prisoner progess through increasing levels of freedom within the detention facility. For the first nine to twelve months of sentence, a prisoner was held in solitary confinement and a focus was made on moral and religious instruction.

Transfer to a public work prison followed, according to physical condition, where a reward/privilege system operated with the ultimate aim of moving into the third stage of the sentence, which was unique to the Irish system.

Prisoners received little supervision, and were held in small communities in portable huts. Subject to satisfactory conduct, they were released on licence.

By 1877, when legislation replaced the Convict Prisons Board with the General Prisons Board, there were four national convict prisons, 38 county prisons and 98 bridewells. The following year, more than 45,000 served sentences in the county prisons alone, and one in three was a woman.

Thereafter, the prison population fell in line with the general exodus from Ireland as emigration of young people and families became the norm.