- Home ›

- Irish emigration ›

- The journey

The journey to Ellis Land, New York

The journey to Ellis Island, the New York immigration reception point from 1892, usually began with receipt of a pre-paid ticket from a family member already settled in America. Those that could afford to buy their fare themselves were small in number. Steerage fares between 1880 and the start of World War 1 held fairly steady at £4-£5 which was equal to half the annual income of a labourer.

Ellis Island - the view from the water

Ellis Island - the view from the water Ellis Island - the view from the water

Ellis Island - the view from the waterThe problem for many of those who wanted to emigrate was that they couldn't find any regular employment in the first place. Without steady income, saving such a fare could be difficult if not impossible.

The pre-paid ticket was, then, an essential feature of the continuing exodus from Ireland. Without it, much smaller numbers would have made the journey to Ellis Island and America.

There were, however, what we now call 'standby' tickets. They were cheaper than reserved tickets and could be bought by those who were prepared to wait. Such price variations were advertised through newspapers and a dense network of shipping agencies.

'Through' tickets were also available. For example, the Lanagan family of Antrim received a pre-paid ticket to Rochester, Pennsylvania, in 1903. Bought in the USA, it cost a total of $75 10c for Robert, his wife Margaret and their infant son.

The journey to Ellis Island: reaching the port of departure

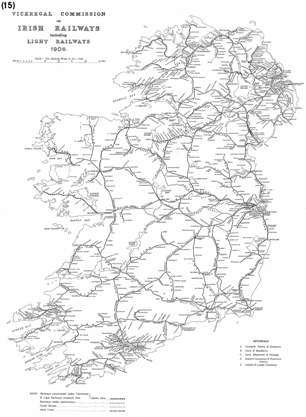

With the cost of passage secured, the next stage in the journey to Ellis Island was getting to the port of departure. Towards the end of the 19th century, some 90% of all Irish emigrants made the sea crossing in iron hulled steam ships.

These were big, with a capital B, compared with the sailing ships that had transported earlier waves of emigrants, and they needed deep water ports, so most of the 'trade' in transatlantic crossings departed from Liverpool in England and then made stops in Queenstown (Co Cork) or Londonderry.

For those with homes in the west/southwest or the north it was convenient to stay at home until the newspapers or the local shipping agent brought news that the ship had been cleared for departure in Liverpool. They could then take a train to Queenstown or Londonderry and save accommodation costs in port.

Liverpool, however, offered passengers the greater choice of crossings and the lowest fares, and the route from Ireland to England was well-established.

For those with homes in the west/southwest or the north it was convenient to stay at home until the newspapers or the local shipping agent brought news that the ship had been cleared for departure in Liverpool. They could then take a train to Queenstown or Londonderry and save accommodation costs in port.

Liverpool, however, offered passengers the greater choice of crossings and the lowest fares, and the route from Ireland to England was well-established.

Although there were other routes to Liverpool, the majority of emigrants travelled via Dublin's Kingstown port (now renamed Dun Laoghaire). This port had had its own rail line to Dublin since 1834 and had been connected to the main network since 1856.

From here, mail, livestock and cargo ships offered deck passage across the Irish Sea, a notoriously fickle stretch of water.

By 1896 the shortest sea crossing, to Holyhead on Anglesey, took under 3 hours, while the steamer to Liverpool took four. In foul weather, the journey could be twice as long.

In 1911, some 80 ships crossed from Kingstown to Britain every week, most of them crammed with migrants. Some already had onward tickets; others planned to save their fare while working in England. No passenger lists were made.

The journey to Ellis Island: via Liverpool

Very few who arrived in Liverpool could go direct to a waiting ship. They were usually told to arrive in the city two days before sailing. Typically, they had to find themselves a place to stay, visit the emigration agents or ship brokers agency, and make sure all was in order for their departure.

What records survive in Liverpool?

- Were your ancestors in Liverpool on a census night? English census returns survive from 1841 and ten-yearly after. They can be searched on a number of websites for a fee, including Ancestry and FindMyPast.

- The National Archives in London holds passengers lists for Liverpool and other British ports from 1890 to 1960s (refs BT26, 27 and 32). The outward list BT27 is online at FindMyPast (see link above).

- Liverpool's Maritime Archive & Library holds a collection of emigrant diaries, letters, photographs and passenger tickets, which can be searched in person.

What records survive in Liverpool?

Were your ancestors in Liverpool on a census night? English census returns survive from 1841 and ten-yearly after. They can be searched on a number of websites for a fee, including Ancestry and FindMyPast.

The National Archives in London holds passengers lists for Liverpool and other British ports from 1890 to 1960s (refs BT26, 27 and 32). The outward list BT27 is online at FindMyPast (see link above).

Liverpool's Maritime Archive & Library holds a collection of emigrant diaries, letters, photographs and passenger tickets, which can be searched in person.

The boarding houses had a reputation for being pretty awful, and the huge bustling city held many dangers for unwitting and unworldly emigrants. All sorts of scams abounded such as charging exhorbitant fees for storing luggage, or overcharging for accommodation.

By the turn of the century, these problems were fewer because the steamship companies started to look after their passengers and limited their exposure to these potential dangers. They were met on arrival and taken to boarding houses and hostels that were either affiliated or owned by the steamship lines.

Unfortunately there are no records of which properties the shipping companies owned, nor are there records of who stayed where (except those who were in port on census nights, of course.... see link box below). Passports or other state documentation was not required for emigrants from Britain and Ireland at this time.

Passengers and their luggage were collected from their accommodation on the day of departure (or the evening before, depending on tides) and taken to the quay where they either boarded their ship or were carried by boat to their ship waiting in the estuary.

Onboard: the class-conscious journey to Ellis Island

The Family Tree

Irish Genealogy Guide

Written by the creator of Irish Genealogy Toolkit and Irish Genealogy News, 'The Family Tree Irish Genealogy Guide' is full of advice, tips and strategies to ease what can be a challenging journey.

Its guidance will be useful to any researcher of Irish heritage, but especially for the target Irish-American researcher who's struggling to work back to Ireland from their immigrant ancestor.

Publisher Penguin Random House.

ISBN: 9781440348808 / 240 pages.

By the end of the 19th century, the biggest transatlantic liners made their journey to Ellis Island with 1900 people onboard. About 500 would be employees and about 1100 would be steerage passengers. The rest were 'cabin class' passengers.

Steerage had historically been a dark, noisy, smelly, stuffy deck of large bunk dormitories. There was little or no privacy, and access to open deck was limited. From 1895, 'closed' berths began to appear in steerage, and offered some privacy. By the outbreak of WW1, 30-50% of tickets were for this 'New Steerage' arrangement.

Another big change to standards of passage had been the introduction of 2nd class tickets. Known as 2nd Cabin passengers, immigrants were offered improved food (and four meals a day instead of three as in Steerage), improved ventilation and more space. It was a much better option, and came to be recognised as good value, especially by families and single women.

From 1880 to 1897, 2nd class made up just 5% of passengers. From 1898 to 1913 it made up 11% of those making the journey to Ellis Island. Fares averaged £8 (against £5 for Steerage), and was the preferred choice of many Irish-born Americans who had made their first crossing in Steerage; having enjoyed some success in the United States, they were prepared to pay the extra when returning permanently or temporarily to/from Ireland.

For first-class passengers, the journey to Ellis

Island was an opulent and luxurious experience. Grand Saloons, flamboyant

ballrooms and top-quality dining were available to those who could afford the

£25 fare. Most of the ship's 500 staff were assigned to cater to the cares and

whims of this group.

The journey to Ellis Island: arrival in New York

In the sailing ships of the middle 19th century, the crossing to America or Canada took up to 12 weeks. By the end of the century the journey to Ellis Island was just 7 to 10 days. By 1911 the shortest passage, made in summer, was down to 5 days; the longest was 9 days. With conditions having improved (although they were by no means extremely comfortable for those in steerage), the transatlantic crossing was no longer seen as a one-time ordeal.

So as the ships entered New York harbour, and the Statue of Liberty came into view, passengers probably felt less trepidation and more simple excitement. The journey to Ellis Island still had a few hours to run for most, however.

The steamship would dock at either the Hudson or East River piers to disembark its first and second class passengers.

The better-off simply passed through Customs at the pier and were free to go.

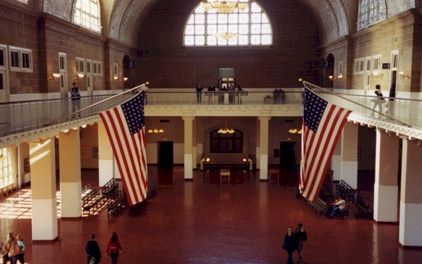

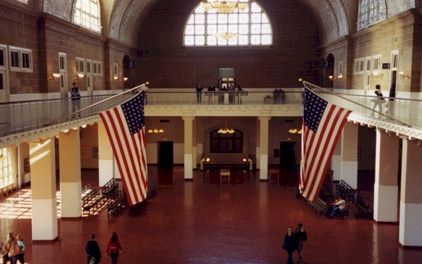

The Great Hall of Ellis Island, where immigrants were registered and examined.

The Great Hall of Ellis Island, where immigrants were registered and examined. Ellis Island's Great Hall, where immigrants were registered/examined.

Ellis Island's Great Hall, where immigrants were registered/examined.For Third-class or Steerage passengers, the final part of their passage was made by ferry or barge to Ellis Island where, in the Great Hall, they had to undergo three to five hours of medical and legal inspections. (Since both inspections were fairly cursory, this period was largely spent waiting to be called forward.) The legal inspection involved checking the immigrant's identity against the ship's manifest which had been prepared by the shipping company before departure in Ireland/England.

They were then free to enter the United States and to begin their new life.

The records of the 51million people who made the journey to Ellis Island from 1892 to 1957 have survived and are available online and free at www.libertyellisfoundation.org.

Mary's journey

My grandfather's eldest sister, Mary, who made the journey to Ellis Island in October 1901, was one of thousands who received a pre-paid ticket. Aged seventeen, she appeared in the 1901 Irish census a few months earlier with no form of occupation, despite her formal education having ended two years previously.

She was probably more than aware that her chance of finding work was limited if she remained at home. My family lived in the southwest of Cork and subsisted on a small patch of garden. On the 1901 and 1911 censuses her father described himself as an egg dealer which sounds a lot grander than the reality. They had a few chickens and sold eggs from a cart at Rosscarberry market. He got labouring jobs as and when he could.

Mary was one of five children still living at home, my grandfather and his brother having secured junior but welcome employment with the Post Office in London. Her big brothers sent money home but they were still little more than kids themselves and their pay would have not stretched to much. Mary's prospects were bleak, and there would certainly not have been any spare cash for buying a transatlantic fare.

When her father's sister Bridget Cotter sent notice of a pre-paid passage, Mary must have experienced mixed feelings. Here was her chance for adventure and opportunity. The price, for her, was leaving behind her family and all that was familiar.

She didn't know it when she said goodbye to her family at Clonakilty rail station in October 1901, but she would never again see her parents, her little sisters or her homeland. She died in her 60s.